In recent years, there has been lots of research around the science of learning and how we learn and retain information.

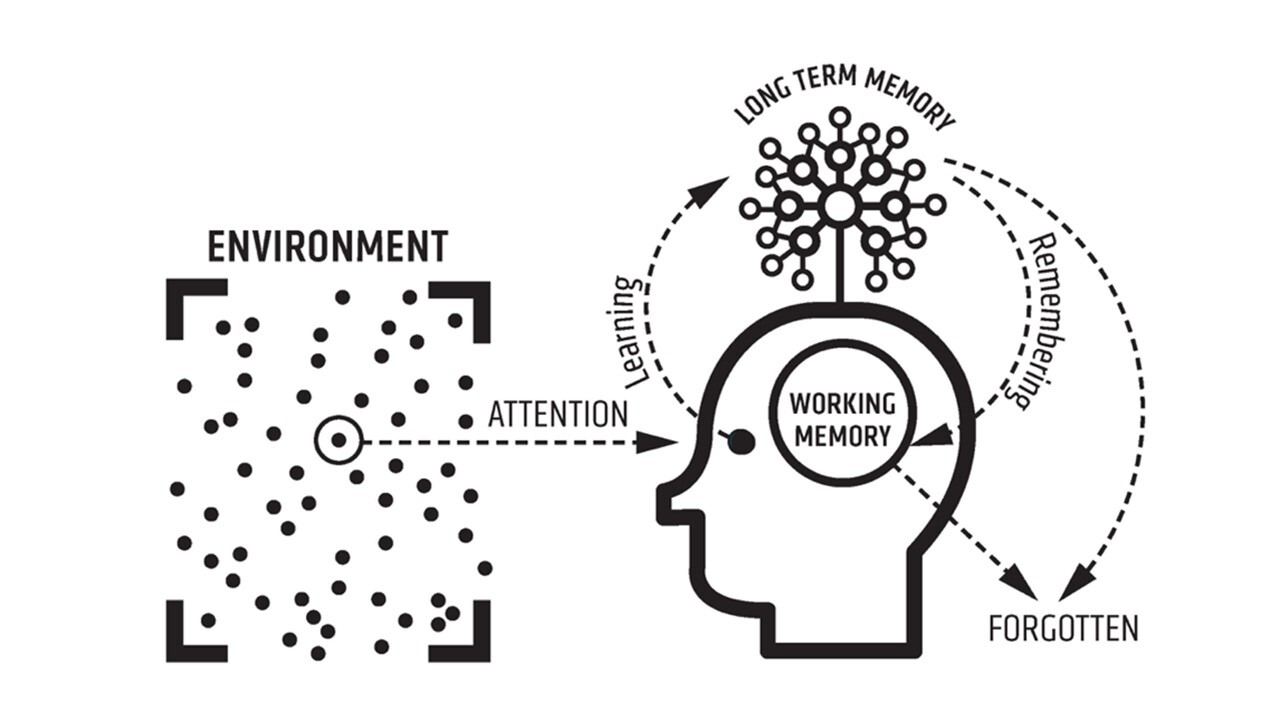

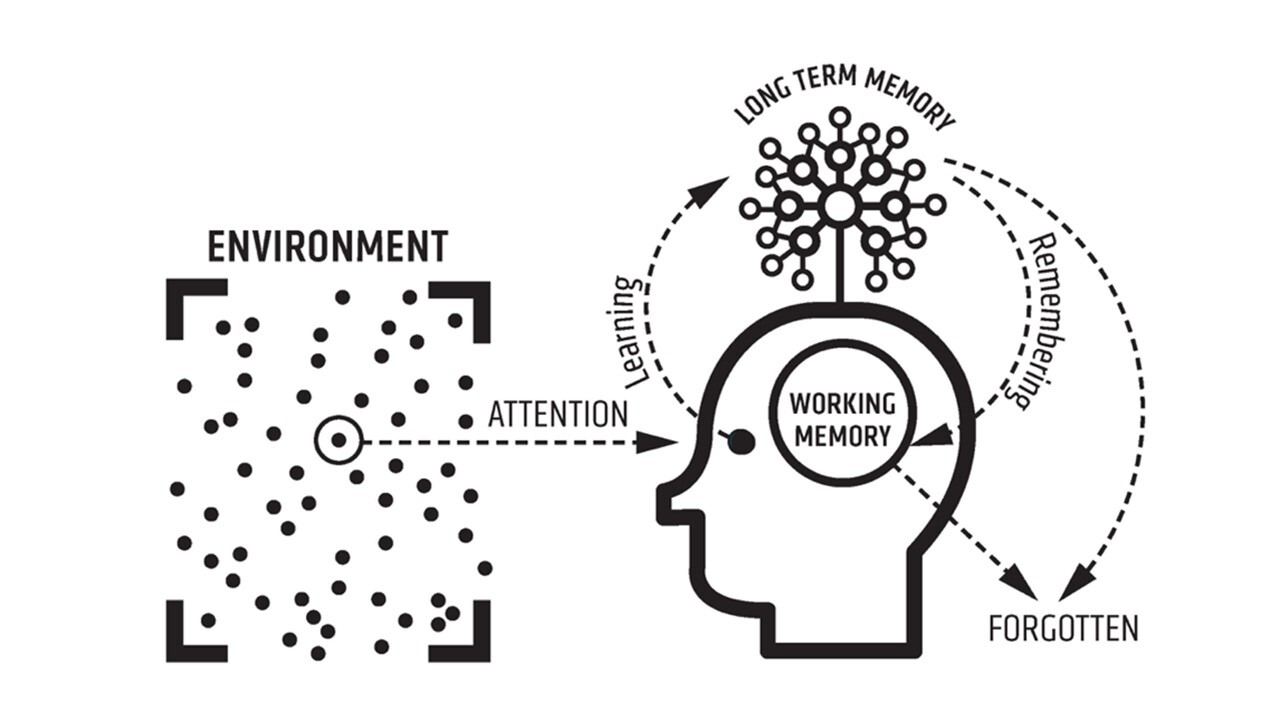

- We have a certain amount of attention to pay, and this can be limited and can dramatically vary depending on the individual or the environment.

- Our working memory is where you do your thinking and where you take in new information. It is finite and we can only absorb a limited amount of information at a given time otherwise it gets crowded (research suggests we can hold 5 things in our working memory at one time). This may be up to 30 seconds.

- Information is processed into our long-term memory through ‘learning’. This long-term memory is effectively unlimited, and we can retrieve information from here back into our working memory as needed in each moment. When we remember something, it comes from here. Learning is therefore a change in your long-term memory. Whatever you think about, that’s what you remember. Therefore, revision activities must require you to think hard.

- Information in our long-term memory is interconnected and linked with prior knowledge. Anything that is not connected or not successfully stored well enough in our long-term memory is forgotten and this is completely natural.

- If students undertake enough retrieval practice, generating the information in our long-term memory, it increases a level of fluency within the subject. Practice makes perfect!

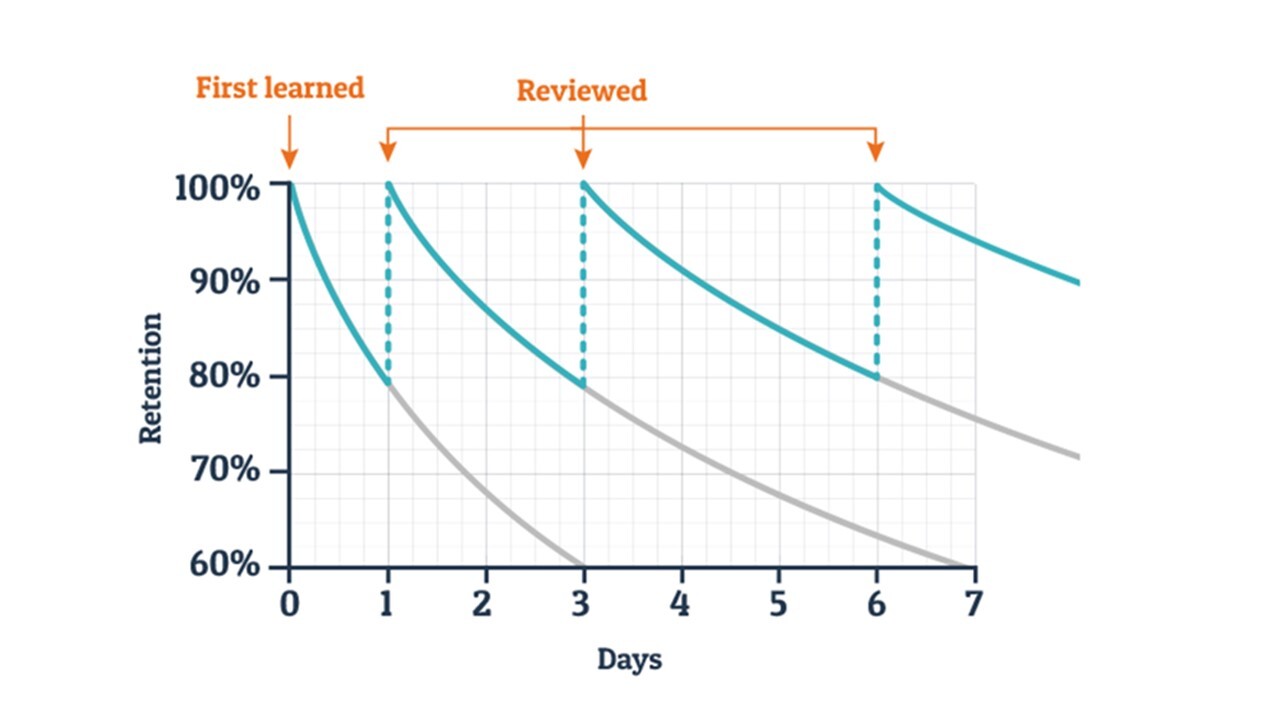

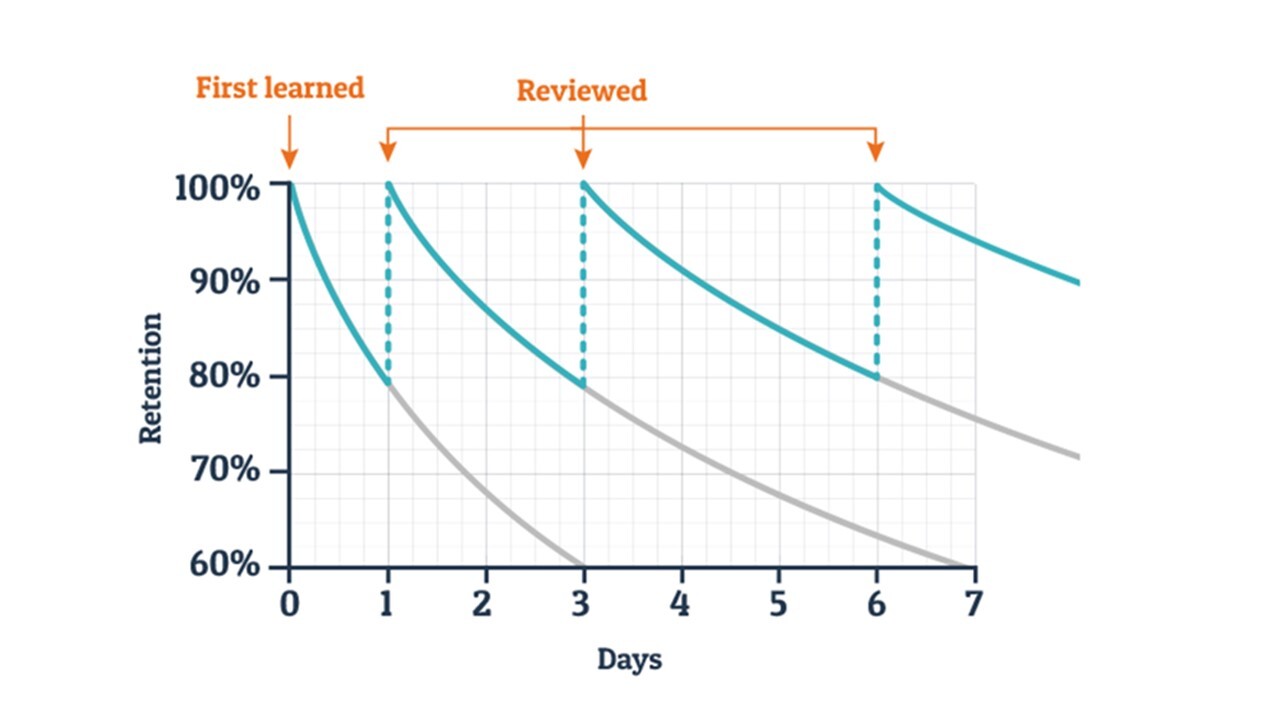

Forgetting is completely natural. Research has shown that over time you forget a majority of what you’ve learnt, and it happens immediately. The following diagram outlines this process and is called the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve (1885).

Typical forgetting curve for newly learned information

Ebbinghaus proposed that humans start losing ‘memory of knowledge’ over time unless the knowledge is consciously reviewed time and time again. He conducted a series of tests on himself which included the memorization of a meaningless set of words. He tested himself consistently across a period to see if he could retain the information. He found that:

- Memory retention is 100% at the time of learning any piece of information (in the moment). However, this drops to 60% after three days.

- A range of factors affect the rate of forgetting including motivation, the meaningful nature of the information, the strategies for revision and psychological factors (sleep for example).

- If each day, repetition of learning occurs, and students take time to repeat information then the effects of forgetting are decreased. According to research, information should be repeated within the first 24 hours of learning to reduce the rate of memory loss.

Practice and retrieval help to break this ‘forgetting curve’ as it strengthens the long-term memory and stops information from fading.

In summary, what do we know about memory?

- Consistent practice and revisiting previous material strengthen memory and boosts learning.

- Our working memory is finite and limited and so overloading this or cramming for revision doesn’t work.

- Information, if not revisited, is ‘lost’ from our memory.

We also think it is important for parents and carers to know effective revision techniques, so that parents and carers can encourage the use of these strategies at home for revision and understand how they can help their child learn effectively.

Parent Revision Booklet

Six Strategies for Effective Revision

- Retrieval Practice: Simply put, recalling information from memory is simple and powerful. Retrieval practice is a learning strategy which makes you think hard and brings information to mind. It is the action of actively retrieving knowledge that boosts learning and strengthens memory. It means trying to remember previously learned information as opposed to simply re-reading it. It builds confidence over time and allows you to identify gaps in your knowledge. Examples include:

- Knowledge quizzing, low stakes testing and multiple-choice tests.

- Completing past paper questions or practice answers.

- Answering verbal questions asked by teacher/peers/parents.

- Summarising, creating flashcards or revision materials where you can ‘test’ yourself.

Knowledge retrival

- Spacing out your revision into smaller chunks over a period of time helps you to remember the material better and ensures you are less stressed with your revision. This ensures you are not cramming as it will overload your memory and make you overconfident. By leaving time between revising and testing, the harder your brain works, the more chance of remembering.

- Interleaving involves switching between ideas and topics during a study session and not revising in blocks of topics. This ensures that you are not studying one idea or topic for too long. Mixing up your revision and chunking it supports learning and strengthens your memory as we know you need to review information over time to reinforce learning. If a subject involves a narrative (story), revise this in one piece.

Spaced practice & interleaving

- Dual Coding is all about combining verbal representations of information (words) with visual representations of information (pictures/diagrams). When we combine these, it is easier for us to understand the information being presented. Importantly, this is not the same thing as learning styles. While students do have preferences, matching these preferences does not help them learn. Instead, we all learn best when we have multiple representations of the same idea. Importantly, make sure the students have enough time to digest both representations. When students are studying, they should use multiple representations and try to explain to themselves how the different representations show the same idea.

Dual coding

- Elaboration: Involves asking “how” and “why” questions about a specific topic, and then trying to find the answers to those questions. The act of trying to describe and explain how and why things work helps students understand and learn. Students can also explain how the topics relate to their own lives or take two topics and explain how they are similar and how they are different. This strategy can be assigned alone or for pairs of students.

Elaboration & marginal gains

- Concrete Examples: Concrete information is easier to remember than abstract information, and so concrete examples foster learning. Importantly, research shows that multiple examples of the same idea, especially with different surface details, helps students understand the true idea the example is intending to illustrate. This is because novices tend to remember surface details. Imagine teaching about scarcity and using airline tickets as an example. Students later may remember scarcity was about flying, but not the rest. Using other examples that have nothing to do with tickets (e.g., water during a drought) and making the link between the examples explicit for the students helps them understand the underlying abstract idea.

Useful Revision Guides:

Year 11 revision resources 2023Mathematics Revision Guide

Year 13 revision resources 2023

Scholarly Habits

Memory and Science of Learning

updated: March 2023